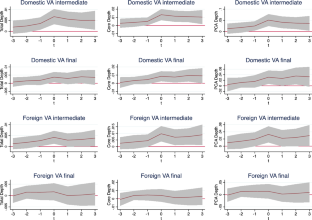

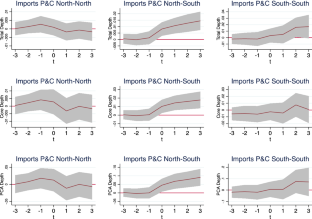

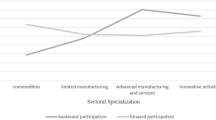

A prominent argument as to why countries sign “deep” preferential trade agreements (PTAs) is to foster global value chains (GVCs) operations. By exploiting a new dataset on the content of PTAs, this paper quantifies the positive impact of deep PTAs on GVC participation, mostly driven by value-added trade in intermediate rather than in final goods and services. On average, each additional policy areas increases the domestic and the foreign value added of intermediates by 0.48 and 0.38%. Deep PTAs facilitate integration in industries with higher levels of value added. Their content also matters for GVC integration by income group.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Price includes VAT (France)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

As is common in the recent trade literature, the term PTAs will be used throughout the paper and is preferred to the term ‘regional trade agreements’ (RTAs) since some of these agreements are not necessarily among countries within the same region or in regional proximity. We will also often refer to PTAs as ‘deep (trade) agreements’, in recognition of the fact that several provisions in PTAs are not preferential in nature (Baldwin and Low 2009).

For a survey of the literature, see Limão (2016). A companion paper by Mattoo et al. (2017) uses the new World Bank database on the content of PTAs to revisit the classic Viner question of trade creation and trade diversion.

Contemporaneous work by Rubínová (2017) and Boffa et al. (2019) also use the new World Bank database on the content of PTAs to analyze various aspects of the relationship between deep agreements and GVCs.

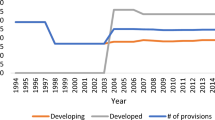

In our analysis we exclude partial scope agreements that cover only certain products. See Horn et al. (2010).Table 13 in “Appendix” presents the list of provisions. More details on the methodology and the data on deep trade agreements can be found in Hofmann et al. (2019). The data are freely available at the following website: https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/content-deep-trade-agreements.

Unless otherwise stated, all provisions that are included in measures of PTA depth are legally enforceable. We also create an index that summarizes the depth of a PTA into three categories: shallow PTA, if it includes fewer than 10 provisions; deep PTA, if it includes between 11 and 20 provisions; and very deep PTA, if more than 21 provisions are included. Results that are obtained with this categorical variable are similar to the one reported for \(TotalDepth_

The components are not weighted averages of the variables in a strict sense since the coefficients (or loadings) that are associated with each variable in each component can also be negative and do not sum to one. In this paper, we use the term weights when referring to the coefficients of the components.

Other components still incorporate important information in the data but their economic interpretation is difficult.

The WIOD database covers 40 countries in the period 1995–2011.The sum of the six above mentioned value-added components do not match exactly the official trade statistics in gross value terms. The difference is due to double counting (column (7)) that tends to increase when goods and services cross borders multiple times. The work of Wang et al. (2013) contributes to a body of the literature that develops measures of the positioning of countries and industries in GVCs (see Fally 2012; Antràs et al. 2012; Antràs and Chor 2013).

Regressions that use gross trade data are estimated for 184 countries between 1995 and 2014.We tested our work on two other trade-in-value-added datasets that are based on the Eora and GTAP Inter-Country Input–Output tables. Despite offering wide country coverage (189 for Eora and 121 for GTAP), these two datasets do not suit our empirical context perfectly, which leads to either non-significant or weakly significant results. The Eora dataset relies on several assumptions to generate the underlying time series for developing countries, which might distort our variables of interest. Being only available for selected years (2004, 2007, and 2011), the GTAP data mutes a substantial amount of variation from our sample. Possibly for this reason, we find that our key result on the relationship between deep agreements and GVC is supported only with weak significance when we use the GTAP database. Results are available upon request.

Data on BITs come from UNCTAD. The exclusion of this variable from the regressions does not affect the results.

The variable \(PTA_Our regression model remains in the category of gravity models, since the country-pair fixed effects soak up the effect of distance.

This assumption may over-estimate the depth of older PTAs; but we believe that the error introduced should be negligible since most of the replaced PTAs are agreements between the European Union and acceding countries.

See Baldwin (2011) and WTO (2011). Results for the other depth variables are qualitatively similar and are available upon request.The smile-curve concept, which was introduced by Acer founder Stan Shih in the early 1990s, asserts that value-added is becoming more concentrated at the upstream and downstream ends of the value chain.

North is defined as the group of high-income WTO Members, while South comprises low- and middle-income and LDC WTO members.

Estimations using the WIOD, which covers only a few developing countries, are similar to this last set of results.

The results for the other depth variables are qualitatively similar and are available upon request.Similar results are also found when regressions are performed using four- and five-year intervals. Results for the other depth variables are qualitatively similar and are available upon request for the data in value added (Table 12).

We are grateful to Richard Baldwin, Michael Ferrantino, Nuno Limão, Aaditya Mattoo, Sebastien Miroudot, Alen Mulabdic, Zhi Wang, and seminar participants at Stanford University, the University of Maryland, the Graduate Institute in Geneva, the University of International Business and Economics (UIBE) in Beijing, the OECD, and the World Bank for helpful comments and suggestions. Errors are our responsibility only. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments that they represent.